The Market Hates Big Cloud Spending. The Data Says The Market Is Wrong.

Hey everyone,

Because there has been an emergence of fear after big tech earnings related to CapEx AI spending, I decided to share my views on this topic and why I believe the fears around it are wrong at this point.

We had earnings from Meta, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon, and all of them increased AI CapEx substantially. Microsoft CapEx went from $63 billion in 2025 to a guide of over $100 billion for 2026; Google (Alphabet) went from $91 billion to a range of $175 billion to $185 billion; Meta went from $72 billion to a range of $115 billion to $135 billion; and Amazon went from $131 billion to a $200 billion guidance for 2026.

At this point, given the massive increases in these CapEx number as an investor, you are either on the side of the group of investors who don’t believe the companies will be able to deliver revenues and profits on these investments, or you are on the side who do believe, and based on that, the future revenue and profit outlooks are very high. Given the stocks mostly sold off on this CapEx news, the »bears« took over, but I don’t agree with them, and this article explains why. In the last part of the article, I also break down which hyperscaler looks best positioned to further accelerate their growth in 2026 and 2027.

The CEOs of all these businesses are not only telling you they believe the profits will be there, they are already showing you growth that came from 2023 AI investments (that keep in mind often were also criticized for being outlandish), and more importantly, they are showing you PROFITS on these AI investments.

Here is what the market has missed.

The Q4 2025 AI Earnings profits were overshadowed by future CapEx numbers

Before we go into the actual numbers, the fact is that we got really strong commentary from nearly all the big tech CEOs on AI revenue and returns from these investments. One might think that they are saying this because it is in their interest, but that is not really true. For most big tech companies like Google and Microsoft, it is actually in their interest for AI progress to grow at a more gradual rate than the exponential one it has today. The reason is that a lot of their business lines face disruption risk (Google Search, Microsoft software business, etc.). So these strong commentaries from these CEOs should be taken differently than comments coming from startups like OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI, who, in some way, have to project the fast growth curve of AI as they need to raise new capital rounds, so they naturally have to project confidence both in terms of companies as well as the market in general.

We got some interesting comments from Amazon, which has a history of being very strict and efficient in its data center business. Andy Jassy confirming multiple times the confidence in the return on invested capital:

»We have deep experience understanding demand signals in the AWS business and then turning that capacity into strong return on invested capital. We’re confident this will be the case here as well.«

»We have, I think, a fair bit of experience over the years in AWS of forecasting demand signals and doing it in such a way that we don’t have a lot of wasted capacity and that we also have enough capacity to serve the demand that’s there.«

»And I think we’ve also proven with AWS over the years in how we build data centers and how we run them and how we invent in there, if you think about our chips and our hardware and our networking gear and how we’ve invented in power that this isn’t some sort of quixotic top line grab, we have confidence that we -- that these investments will yield strong returns on invested capital. We’ve done that with our core AWS business. I think that will very much be true here as well.«

Jassy even confirmed that as soon as they bring new capacity online, it’s essentially sold out:

»And what we’re continuing to see is as fast as we install this capacity, this AI capacity, we are monetizing it. And so it’s just a very unusual opportunity. And so we see that following the same sorts of patterns we saw in the early days of our core AWS investment. I’m very confident we’re going to have strong return on invested capital here.«

From the historic understanding of Amazon in terms of words, they often underhype, so a comment like this was very telling:

»I think this is an extraordinarily unusual opportunity to forever change the size of AWS and Amazon as a whole.«

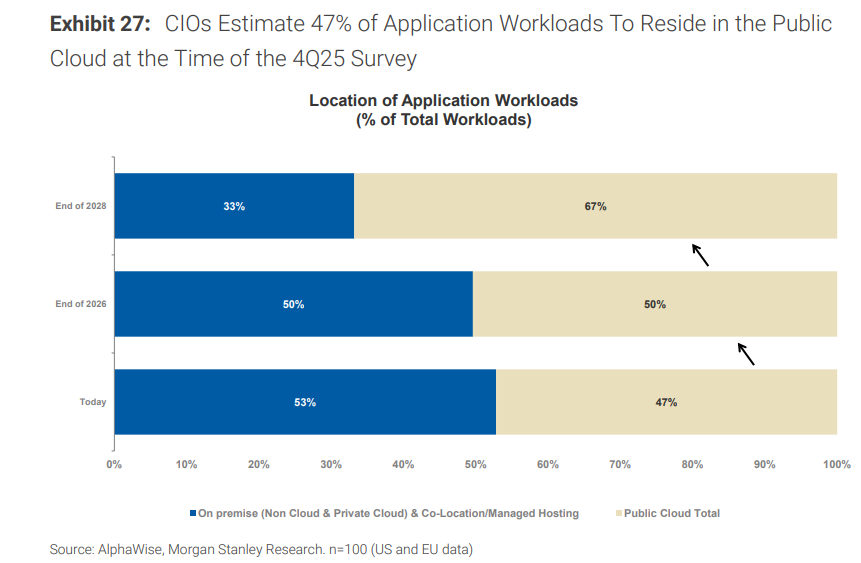

Remember, just before AI, there was a big trend of companies moving workloads from the cloud back to on-prem because they thought many cloud workloads were too expensive. Now companies are realizing that AI workloads will need to be on cloud, because companies don’t have the resources or even the possibility to manage complex data centers with liquid cooling requirements (most data centers don’t have the option of liquid cooling), GPU utilization rates and managing multiple AI accelerators (Nvidia GPUs, AMD GPUs, ASICs like TPUs, Tranium). Because of this, they have also started moving non-AI workloads to the cloud, as the data needs to be close to the AI workloads for them to run properly.

»We’re continuing to see strong growth in core non-AI workloads as enterprises return to focusing on moving infrastructure from on-premises to the cloud«

Because of AI, the cloud providers have increased their cloud » lock-in « and are growing even non-AI workloads.

I already talked about this trend just a few weeks ago in my Q4 alternative report article, where we showed this chart confirming that companies are going to move to the cloud at an accelerated pace again over the next 2 years:

But it wasn’t just Amazon talking about AI returns; the other Big Tech companies were, too. Meta gave a lot of color on how AI investments are already showing up in their business results:

»In Q4, we doubled the number of GPUs we used to train our GEM model for ads ranking. We also adopted a new sequence learning model architecture, which is capable of using longer sequences of user behavior and processing much richer information about each piece of content. The GEM and sequence learning improvements together grow a 3.5% lift in ad clicks on Facebook and a more than 1% gain in conversions on Instagram in Q4.«

»Instagram Reels had another strong quarter with watch time up more than 30% year-over-year in the U.S. Engagement is benefiting from several optimizations we made to improve the quality of recommendations including simplifying our ranking architecture to enable more efficient model scaling.”

On Facebook, video time continued to grow double digits year-over-year in the U.S., and we’re seeing strong results from our ranking and product efforts on both feed and video surfaces.«

»The optimizations we made in Q4 drove a 7% lift in views of organic feed and video posts on Facebook, resulting in the largest quarterly revenue impact from Facebook product launches in the past two years.«

Meta is seeing results from AI in both better ad targeting and engagement trends. The results actually »revived« Meta’s core and oldest platform, Facebook, which is seeing growth rates it hasn’t seen in years. But AI is opening up other avenues of growth at Meta:

»Another area we’re deploying AI to improve performance is ad creative. The combined revenue run rate of video generation tools hit $10 billion in Q4, with quarter-over-quarter growth outpacing the increase in overall ads revenue by nearly 3x.«

The returns are not only affecting their revenue but also the productivity of their teams:

»Since the beginning of 2025, we’ve seen a 30% increase in output per engineer with the majority of that growth coming from the adoption of agenetic coding, which saw a big jump in Q4. We’re seeing even stronger gains with power users of AI coding tools, whose output has increased 80% year-over-year. We expect this growth to accelerate through the next half. «

But despite these gains, Meta is telling us that it’s still very early as they are still using a limited amount of LLMs, as they have to either optimize them with SLMs because of compute limitations, or are still in the early stages of deploying these LLMs through their product stack:

»We’re also working on merging LLMs with the recommendation systems that power Facebook, Instagram, Threads and our ad system. Our world-class recommendation systems are already driving meaningful growth across our apps and ads business, but we think that the current systems are primitive compared to what will be possible soon.«

»We don’t typically use our larger model architectures like GEM for inference because their size and complexity would make it too cost prohibitive. So the way that we drive performance from those models is by using them to transfer knowledge to smaller lightweight models used at run time. But I would say that we think that there is room for our larger models to benefit from having more compute.«

All of this resulted in Meta giving the highest revenue growth guide in almost 5 years. And despite the higher CapEx guide and costs stemming from both OpEx (new AI team costs + compute costs on public cloud providers) and higher amortization costs, Meta confirmed that they expect 2026 to deliver operating income above 2025.

In terms of Google, Google Cloud grew 48% YoY, one of the highest growth rates among businesses of this scale. Google Search actually grew 17% YoY, which is another growth rate for Search that hasn’t been seen for quite some time. On the call, management even commented that Search saw more usage in Q4 than ever before, as »AI continues to drive an expansionary moment for Search«.

But even ignoring all the commentary from these companies’ management, let’s look at the hard numbers.

First, starting with revenue. All three hyperscalers are essentially selling all the compute they have available; if they had more, they would grow revenue even faster.

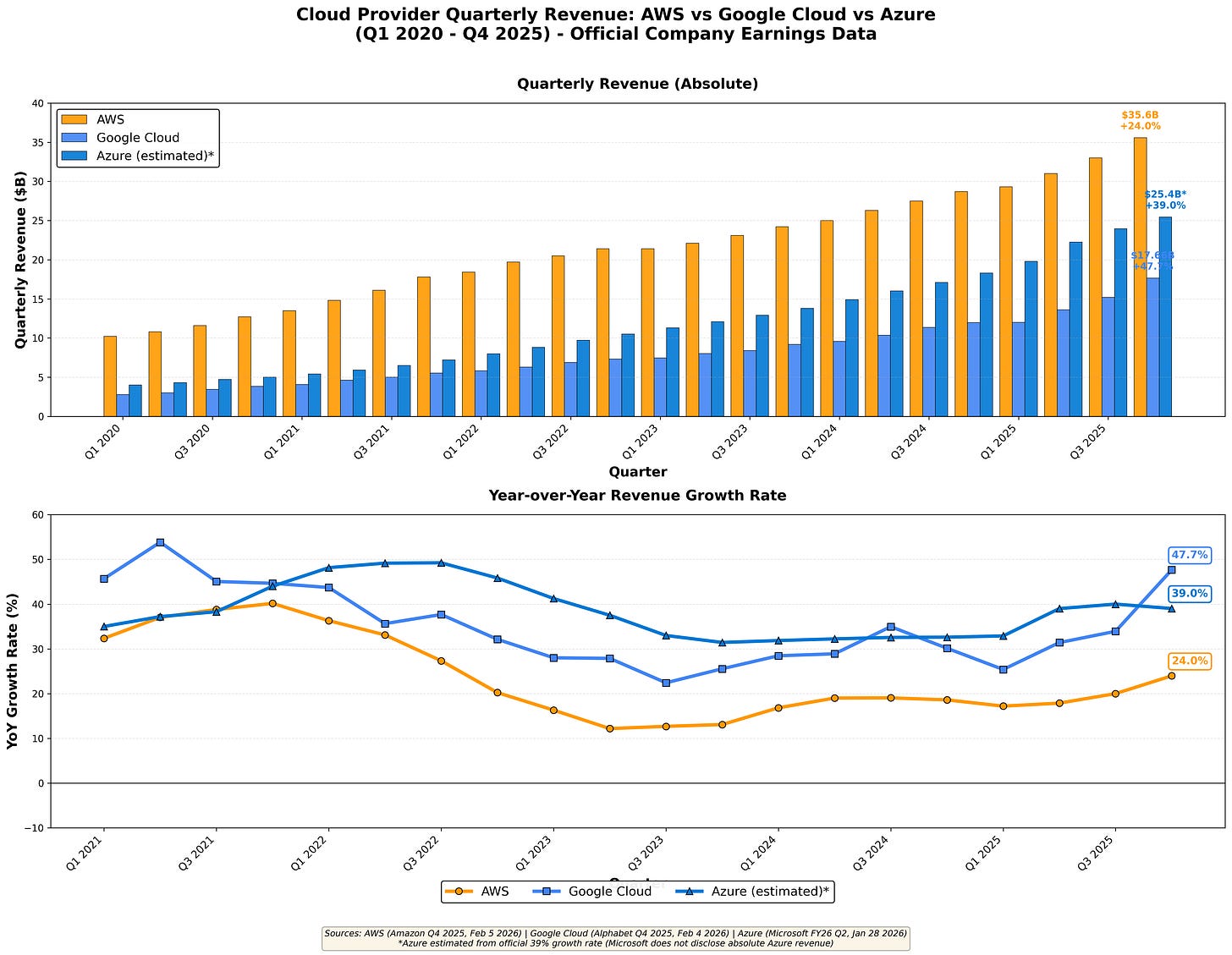

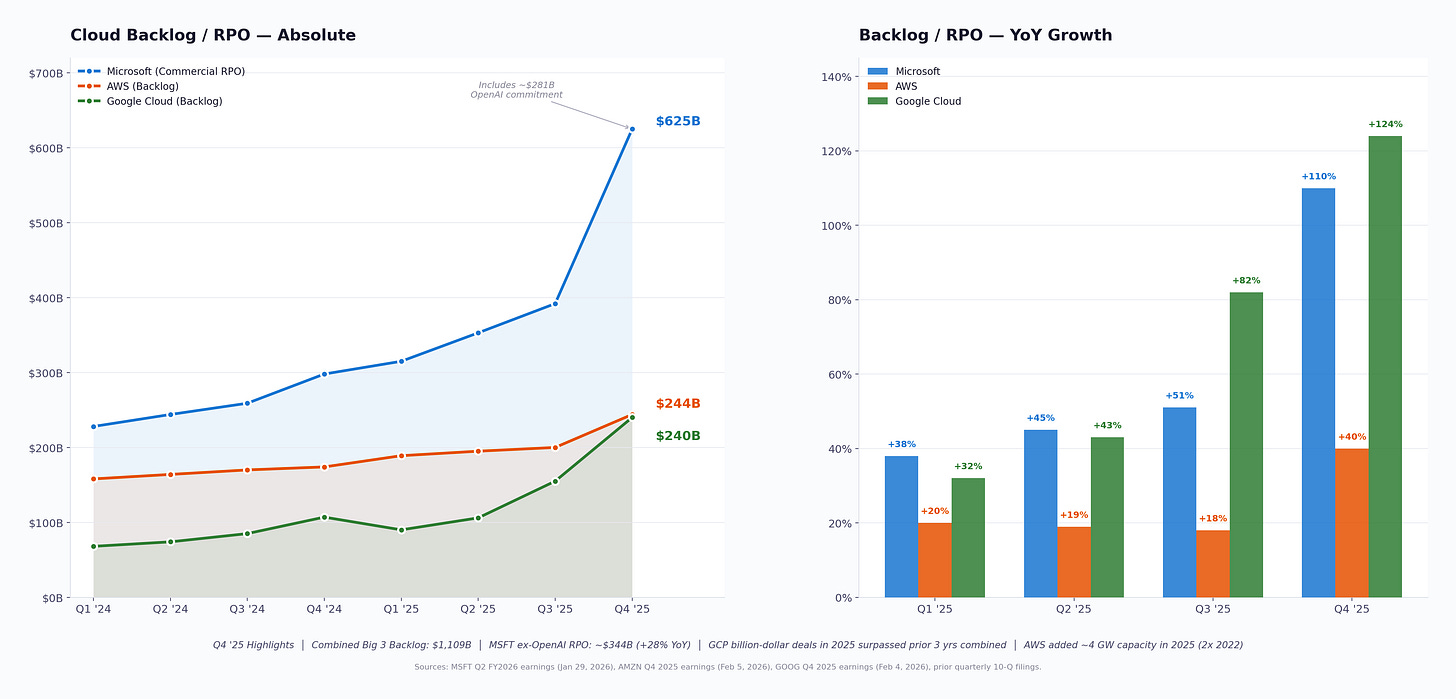

AWS grew 24% YoY, Azure grew 39% YoY, and Google Cloud grew 48% YoY. Their backlogs are growing even faster.

From the current revenue growth on top of the backlogs, we can clearly see that the hyperscalers are again growing significantly due to AI workloads. The standout in the quarter, as we correctly pointed out in our alternative data report before earnings, was Google Cloud. It is clear that the AI spend in the past is translating to real revenue growth. So the notion that these companies are spending only on CapEx and we can’t see revenue from it is false. Now, the questions and the narrative in the market are that the profits won’t come from this revenue stream.

The main argument for this thesis is that AI workloads will have a lower long-term profile margin, and, secondly, that people are calculating returns based on projected CapEx guides and comparing them to current revenues.

If we first tackle the CapEx argument. It is important to understand that the CapEx a hyperscaler spends on a data center this year will be utilized over a 2-year period, as it takes around 2 years to build and operationalize a data center. So when people look at 2025 revenue growth for the hyperscalers, they should translate that into CapEx spent in 2023, not in 2024 or 2025. When we are in a period like we are today, when YoY CapEx growth (estimates for 2026) are +53% (AWS), +93% (Google Cloud), +59% (Microsoft Cloud), the math doesn’t make much sense when we compared to 2025 revenues, because we should be really comparing 2023 CapEx to 2025 revenue growth.

If we look at 2023 CapEx numbers, we can see that both Microsoft and Google increased CapEx in 2023 by 17.5% to $32.3B and $28.1B vs 2022 levels, while Amazon reduced CapEx by 17% YoY to $52.7B, although based on my calculations, only a -10% reduction of CapEx in AWS to $24.8B. Now, if we compare those CapEx numbers to the revenues generated by hyperscalers in 2025, the math makes a lot of sense, as yearly revenue additions are outpacing CapEx spending.

Even for the most conservative investors out there, we can take the example of Google Cloud and even take the 2024 CapEx and compare it to the Q4 2025 results:

Google’s 2024 CapEx was $52.5 billion, with roughly $42 billion going to technical infrastructure (cloud/AI). Google Cloud grew from $48 billion (2024) to $70.8 billion (2025)—a $22.8 billion increase.

At the new 30.1% operating margins:

$6.9 billion in first-year operating income from 2024 CapEx

Add depreciation (as operating margin already includes that): +$7.0 billion (6-year schedule at Google)

Total first-year cash: $13.9 billion

First-year return: 33%

But here’s where Google’s trajectory gets interesting. They went from 5% margins (2023) to 17.5% (Q4 2024) to 30.1% (Q4 2025). If margins stabilize at 30% (which I actually think will grow even further) and they run that 2024 infrastructure for five years:

Cumulative OI: around $45 billion

Add depreciation: +$42 billion

Residual value (data center shell): +$8 billion

Total: $95 billion on $42 billion invested

ROI: 126% over 5 years, or a 18% IRR

And that still assumes growth moderates significantly from the current 48% YoY pace, while the margin stays at the 30% level and doesn’t improve.

With the increased pace of 2026 CapEx growth, the hyperscalers are essentially telling us what the revenue additions and, with it, growth rates will be for 2028.

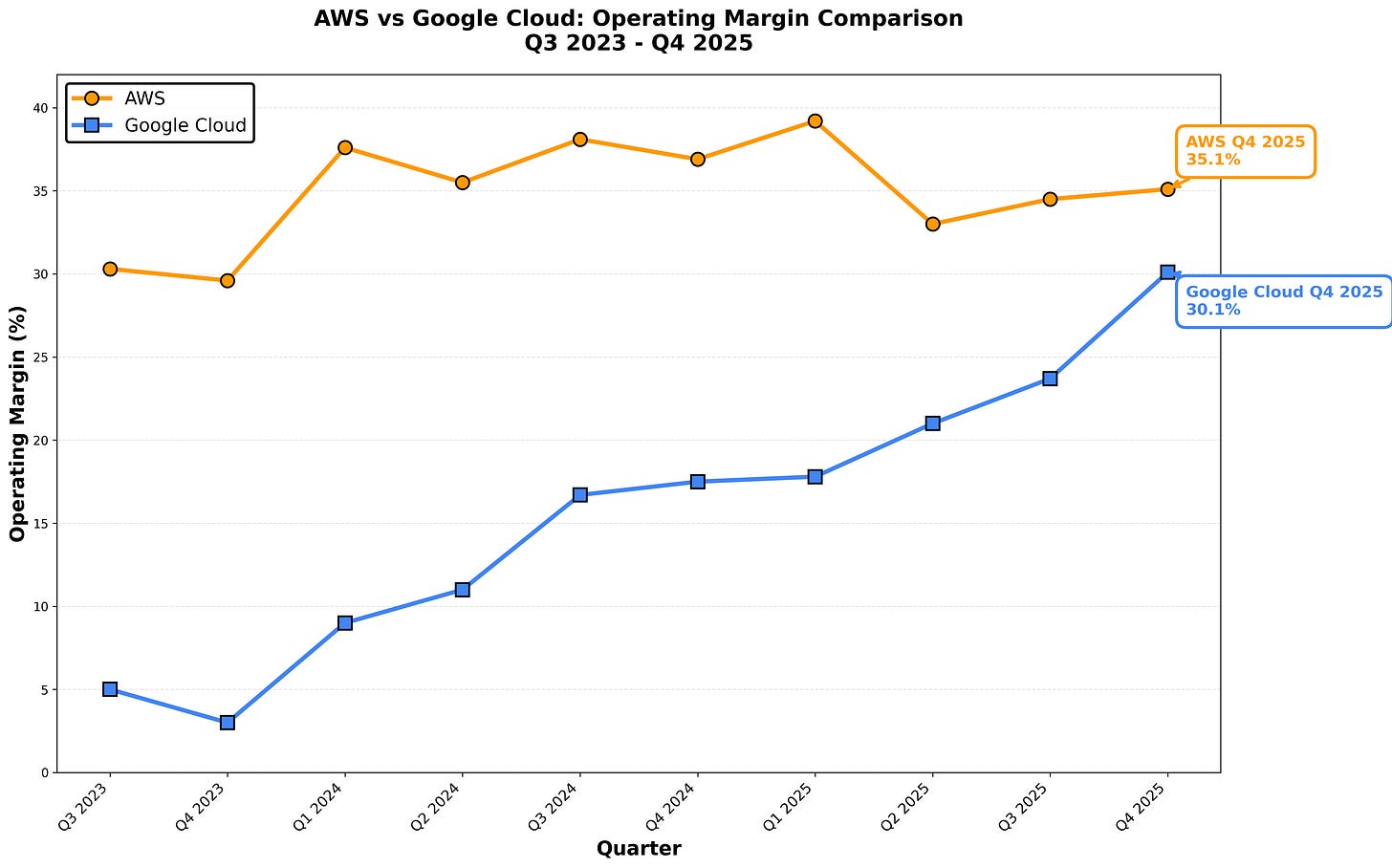

Moving to the argument that the long-term margin on AI workloads will not be good compared to the pre-AI period. The numbers so far do not suggest this at all. Here is a look at AWS and Google Cloud’s operating margins over the last quarters, where AI workloads accounted for the majority of growth.

The operating margin either held up in the same range as AWS (where the % of AI workloads compared to others is still smaller) or increased significantly at Google Cloud, where AI workloads are a bigger piece of the pie. Here, we have to acknowledge that Google Cloud is not only GCP, but nonetheless, commentary from management in all the latest quarters has been that GCP growth rates are even higher than total Google Cloud growth rates, so we should have seen a trend of lower operating margin, not higher, if AI workloads carried a low margin profile. An additional point to consider is also that a lot of the AI workload spend at GCP in this period were coming from Anthropic, which is one client that has much more negotiating power in terms of pricing then a bunch of smaller clients where the cloud providers are moving now as inference AI workloads start to take up more space as companies move their AI use-cases to production. Important in the context of margin is also the statement made by Google on its last earnings call:

“We were able to lower Gemini serving unit cost by 78% over 2025 through model optimizations, efficiency and utilization improvements.”

What this tells us is that as these hyperscalers get even larger, they can optimize and squeeze more out of existing infrastructure. While some of those cost optimizations will be passed on to the cloud client, it is very clear that the ones with the most scale will also be able to use them to further expand their margin profile. Scale, but also custom ASICs play a key role here.

Custom ASIC is the key

Another strong argument that I already laid out in many of my previous articles is the custom silicon that cloud providers are designing. I continue to believe that this will be a critical element for any cloud provider to maintain healthy margins in the long term and avoid becoming overly dependent on a provider like Nvidia, which now has gross margins of almost 75%. In terms of custom ASICs, Google is best positioned with its TPUs, as we already laid out in the TPU article, followed by Amazon with Tranium. While Microsoft’s efforts here lag those of the other two, it is important to note that Microsoft also owns full IP rights to the custom ASICs that OpenAI will develop.

No surprise that on the Amazon earnings call, Tranium was mentioned 27 times, while Nvidia was not mentioned at all. We got even so far that the CEO called out specifically Amazon’s chip business and segmented revenue for us as a separate category:

»I think people know about our chips capability and our chips business, but I’m not sure folks realize how strong a chips company we’ve become over the last 10 years.

If you look at what we’ve done with Trainium, if you look at what we’ve done with Graviton, which is our CPU chip, which is about 40% better price performance than comparable x86 processors, 90% of the top 1,000 AWS customers are using Graviton very expansively. If you combine Trainium and Graviton, it’s well over a $10 billion annualized run rate business, and it’s still very early there.«

Even though they lag from a product perspective, Microsoft also talked about its custom ASIC business very early in the call:

»Earlier this week, we brought online our Maia 200 accelerator. Maia 200 delivers 10-plus petaFLOPS at FP4 precision with over 30% improved TCO compared to the latest generation hardware in our fleet. We will be scaling this starting with inferencing and synthetic data gen for our Superintelligence Team as well as doing inferencing for Copilot and Foundry.«

Custom silicon is what ensures hyperscalers can control their margin profile and market share, even in a more heated market where neoclouds and companies like Oracle have entered.

Investors are questioning the AI compute demand, but in reality, we are just getting started

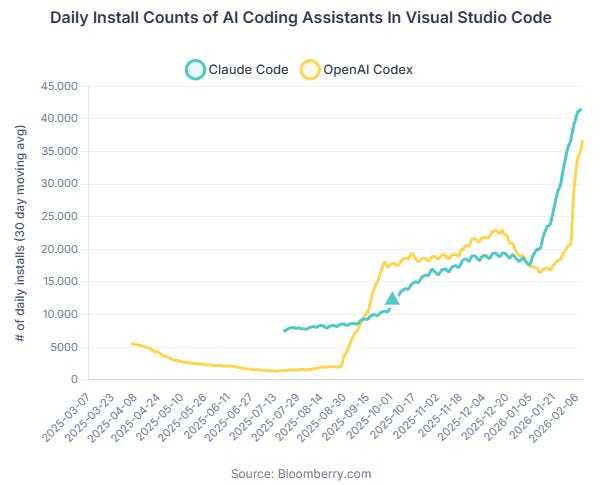

A lot of investors are looking at the +$600 billion in combined hyperscaler CapEx projected for 2026 and questioning whether this is too much. What most people are missing is that we are still in the very early innings of AI compute demand, and the data backs this up. Right now, coding and developer tools have emerged as the single breakout vertical for AI. For those who don’t follow the industry closely or took a break in January, the difference in usage in 1 month is staggering. Daily install counts on VS Code basically more than doubled in just one month, whereas usage is growing even faster. Here is data from the usage of VS Code for Anthropic’s Claude Code and OpenAI Codex. The demand is going off the charts as developers are now not using these LLMs as tools anymore, but as junior to mid programers, where they now only review the code after the AI:

Here’s the thing, though: coding is essentially one vertical. And it’s already consuming an enormous share of the available inference compute. Now think about what happens when finance, legal, healthcare, customer operations, and other enterprise verticals start scaling their AI workloads to the same degree. According to Menlo Ventures, enterprise AI investment tripled from $11.5 billion to $37 billion in just one year, yet only 16% of enterprise deployments today qualify as true AI agents—most are still fixed-sequence workflows. We are nowhere close to saturation. McKinsey’s data shows 78% of organizations are now using AI in at least one business function, but the actual conversion to heavy inference workloads across non-coding departments is still nascent. These numbers are tiny compared to where coding already is.

The market is pricing in CapEx as if coding-level adoption is the ceiling, when in reality, it is the floor.

These aren’t businesses lighting money on fire. These are businesses generating 30-35% operating margins on the largest infrastructure buildout in corporate history.

The custom chip businesses (Trainium, Graviton, TPUs) are growing triple-digits and creating structural moats that compound over time.

The market is treating this like the 2000 fiber glut. That was infrastructure built for demand that didn’t exist.

This is infrastructure being absorbed as fast as it’s deployed. Hyperscaler CapEx isn’t irrational exuberance. It’s the most rational investment decision these companies can make. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google aren’t hoping for AI to work out. They’re reporting the P&L that shows it already has.

Not all hyperscalers will be able to capture market share this year, though. The limiting factor is availability.

Based on the past capacity commitements I calculated which cloud provider should grow the fastest in 2026 and beyond, and here are the numbers: